Genovese was a ruthless boss who ruled with an iron fist, but his grip began to loosen throughout the 1960s. He was sent to prison for 15 years in 1959 on what were thought to be trumped-up heroin charges, and though he maintained technical control of his family, a panel of three other men made the daily decisions.

Genovese died in prison in 1969, and leadership passed to Philip “Benny Squint” Lombardo, Gigante’s associate from his early years in the old Luciano family. Lombardo used front men to act as supposed bosses (and take the hits and prosecutions that frequently came with the job) while he served as the real power. Mob informants and turncoats repeatedly ratted him out as the real head of the Genovese family, but rivals and the feds continued to focus on the patsies.

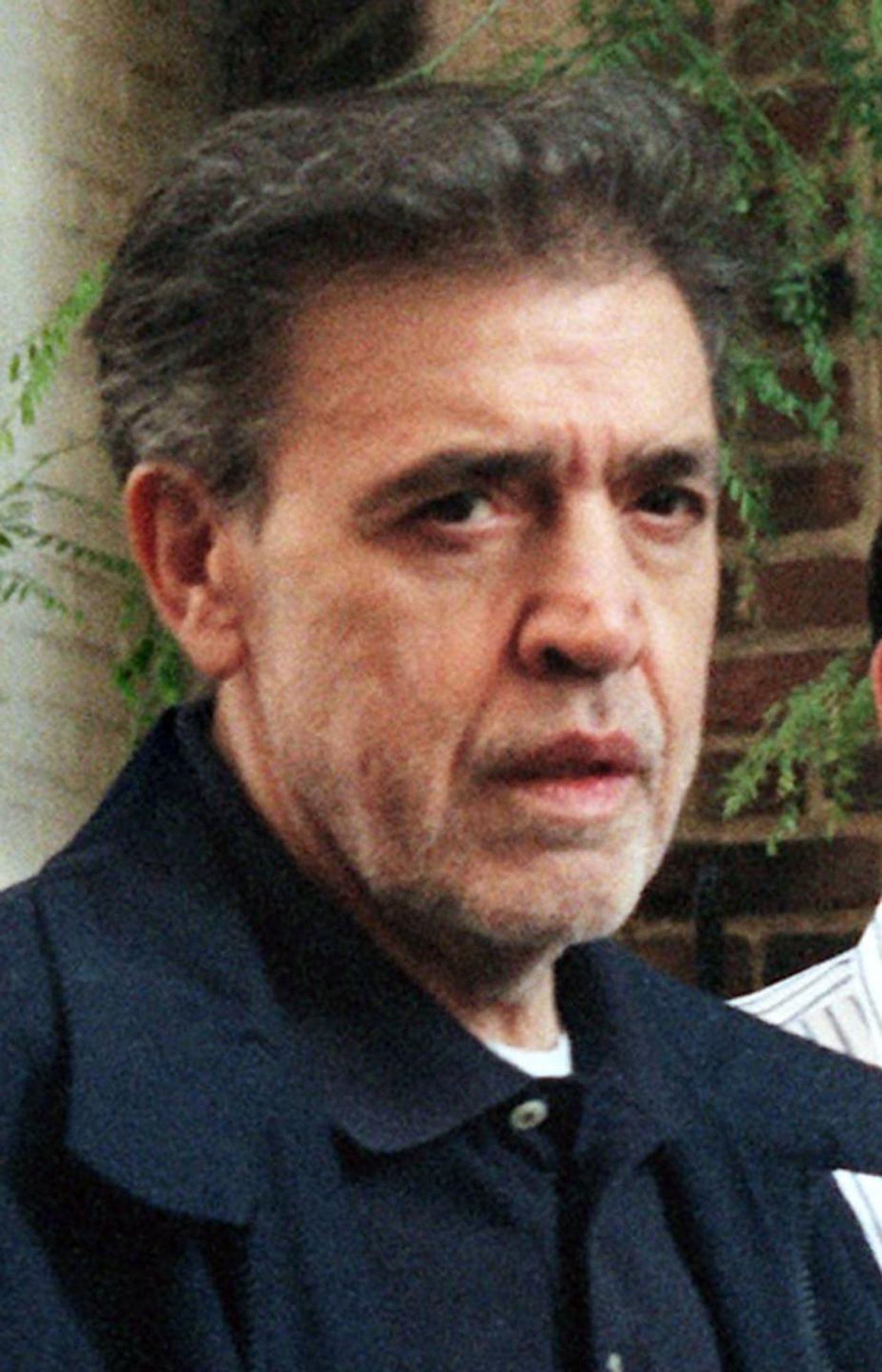

Lombardo stepped down in 1981 due to failing health, and he handed the reins to Gigante. It marked a stunning transformation: A low-rent boxer and failed hit man had somehow risen to one of the top positions in the American mafia. Asked about his mental abilities, his brother Louis, the priest, claimed Vincent had once tested at an IQ level of just 69. His mother told he was a mob boss, responded,

“Vincenzo? He’s the boss of the toilet!”

Gigante followed in Lombardo’s secretive footsteps. As he took power, mobster Anthony “Fat Tony” Salerno was formally named front boss to draw heat away from Gigante, and it worked. The feds focused on Salerno, sending him away for 100 years in 1986 on charges of murder and racketeering.

Gigante used his new position to strengthen the family’s control of organized crime in much of New York City, especially Lower Manhattan. He extended its labor racketeering efforts; took control of projects at the Jacob K. Javits Center and the New York Coliseum; muscled into the drywall, concrete and garbage businesses; exerted more influence over waterfront industries; and expanded gambling and drug trafficking enterprises.

At the same time, Gigante began to restructure the top layers of the mob to insulate himself from his enemies. Like Lombardo, he ran a paranoid operation. At first he followed Lombardo’s lead, using Salerno as a front man, but eventually, the FBI caught on, and ultimately, every gangster in New York knew Gigante was the real don.

With Salerno in prison, Gigante set up a new scheme. He used a so-called “street boss,” Liborio Bellomo, to run the day-to-day business, and a messenger, Dominick Cirillo, to run communications to other mafia members. That way, it was harder for the feds to link Gigante directly to his crimes. He was paranoid, but his tactics worked. Gigante managed to stay out of prison longer than any of his fellow dons, and he was never picked up on a wiretap.

Gigante had little contact with most of his soldiers. He issued orders through his underboss, Venero “Benny Eggs” Mangano, who is believed to of held that position until his death in 2017. Gigante was surrounded by a small group of close associates. He only spoke in whispers and avoided the phone. Any mention of his name by one of his soldiers was grounds for execution – instead, they were required to point to their chins or make a “C” using their fingers.

Like his predecessors, Gigante had no aversion to violence. He ordered many murders as the boss, both in and out of the Genovese families – including the deaths of gangsters in Philadelphia who had killed their boss without his approval.

Gigante eventually rose to the highest position in the American mafia (though it’s been unofficial since the 1930s) as the “boss of all bosses,” or head of the commission that governs the five families of New York and the Outfit in Chicago. He was powerful enough, in some instances, to enforce his wishes on other families as evident with the Philadelphia killings.

As don, Gigante found himself in constant legal trouble. But he had a trick up his sleeve, one he had first played in 1969. And it worked surprisingly well. He merely pretended to be crazy.

In his 1969 bribery case, he managed to convince a long roster of psychiatrists, including several elite doctors selected by the government, that he suffered from schizophrenia, psychosis, dementia and other disorders that made him incompetent to stand trial. To make his symptoms more convincing, Galante’s mother, who was in on the ruse, confirmed to the doctors, Galante had suffered a lifetime of mental trouble.

Gigante, whose antics earned him such nicknames as “The Oddfather” and “The Robe,” kept the charade going for decades. He would frequently emerge from his mother’s Greenwich Village apartment dressed in pajamas, a bathrobe, or other tattered clothes and briefly wander the streets with bodyguards before stopping by a local mafia hangout to play pinochle and issue orders.

He pulled out the stops on his insanity game in the early 1990s, when he was indicted on racketeering and murder charges, many of them stemming from the so-called windows case. For a while, it worked, but it eventually failed him.

Throughout the late 1970s and the 1980s, four of the five New York families had run a cartel of companies that controlled the replacement of windows in New York City Housing Authority buildings. They used bribery and extortion to scam millions off the agency, but the feds finally stopped them utilizing a snitch.

Gigante, like many other mobsters, was indicted in 1990 on racketeering, with an added murder charge. But again, he was determined to convince psychiatrists he was unfit to stand trial.

This time, however, things would be different. Turncoats were popping up everywhere, including the notorious Salvatore “Sammy the Bull” Gravano, who testified, along with others, that Gigante was perfectly sane. With the new testimony, Gigante’s ruse didn’t last. In 1997, he stood trial and was convicted of racketeering and conspiracy. The murder charge didn’t stick.

While in prison, Gigante was convicted again, this time on new racketeering charges and obstruction of justice. The feds alleged he was still running the family from prison and had faked mental illness to delay his previous trial.

Gigante could see the rats gathering around him and pleaded guilty on April 7, 2003. He even admitted his madness was an elaborate sham and had been for the past 30 years. In exchange for what many considered abject surrender by a don, Gigante received just three more years added to his sentence. He also secured lighter punishment for his son, Andrew, who was convicted for running mob messages.

The deal was meant to spare Gigante a death in prison, but it didn’t do much good. He began to fall apart in late 2005 and was transferred from prison to a private hospital. When he started to recover, he was returned to a prison facility. He died there on December 19, 2005. His remains are buried in Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn.

To this day, Gigante’s relatives and associates are deeply ensconced in lucrative union jobs on the New Jersey waterfront, where they earn millions of dollars.